Liquid Crystals

In 1888 the Austrian botanist and chemist Friedrich Reinitzer, interested in the chemical function of cholesterol in plants, noticed that the cholesterol derivative cholesteryl benzoate had two distinct melting points. At 145.5°C (293.9°F) the solid compound melted to form a turbid fluid, and this fluid stayed turbid until 178.5°C (353.3°F), at which temperature the turbidity disappeared and the liquid became clear. On cooling the liquid, he found that this sequence was reversed. He concluded that he had discovered a new state of matter occupying a niche between the crystalline solid and liquid states: the liquid crystalline state. More than a century after Reinitzer's discovery, liquid crystals are an important class of advanced materials, being used for applications ranging from clock and calculator displays to temperature sensors.

Mesophases

In a crystalline solid, the molecules are well ordered in a crystal lattice . When a crystal is heated, the thermal motions of the molecules within the lattice become more vigorous, and eventually the vibrations become so strong that the crystal lattice breaks down and the molecules assume a disordered liquid state. The temperature at which this process occurs is the melting point . Although the transition from a fully ordered structure to a fully disordered one takes place in one step for most compounds, this

transition is not a universal behavior. For some compounds, this process of diminishing order as temperature is increased occurs via one or more intermediate steps. The intermediate phases are called mesophases (from the Greek word mesos, meaning "between"), or liquid crystalline phases. Liquid crystalline phases have properties intermediate between those of fully ordered crystalline solids and liquids. Liquid crystals are fluid and can flow like liquids, but the magnitudes of some electrical and mechanical properties of individual liquid crystals depend on the direction of the measurement (either along the main crystal axis or in another direction not along the main axis). Typical liquid crystals have rodlike or disklike shapes. Classes of liquid crystalline states or mesophases can be distinguished according to degrees of internal order.

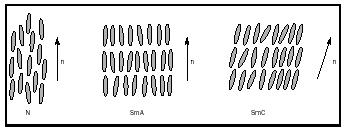

The least ordered liquid crystalline phase for rodlike molecules is the nematic phase (N), in which the long axes of individual molecules have an approximate direction (which is called the director, n). A nematic phase material has a low viscosity and is therefore very fluid. The term "nematic" is derived from the Greek word for thread (after the threadlike microscopic textures exhibited by nematic phase substances). In the smectic phases, the molecules have more order than molecules existing in the nematic phase. Just as in the nematic phase, the molecules have their long axes more or less parallel to the director. Additionally, the molecules are more or less confined to layers. The term "smectic" is derived from the Greek word for soap (owing to the fact that smectic liquid crystals have mechanical properties similar to those of concentrated aqueous soap solutions). The smectic phases are divided into classes based on degree of molecular order; the smectic A phase (SmA) and the smectic C phase (SmC) are the most studied ones. In the SmA phase, the molecules are perpendicular to the smectic layer planes, whereas in the SmC phase they are tilted. Substances assuming these phases have some fluidity, but their viscosities are much higher than that of a nematic phase substance. In Figure 1, the arrangements of molecules in the nematic, smectic A, and smectic C phases are shown schematically. Chiral molecules (molecules lacking a center of symmetry) can assume a cholesteric phase, also called a chiral nematic phase. In this mesophase, the molecules have helical arrangements. The pitch is the distance along a longitudinal axis corresponding to a full turn of the helix .

Typical mesophases formed by disklike molecules are columnar, wherein the molecules are "stacked" into columns. The columns are in turn packed together to form two-dimensional arrays. In addition to the columnar arrangements, the molecules can become ordered in a way that is comparable to a heap of coins spread on a flat surface—the discotic nematic phase.

Displays

By far the most important application of liquid crystals is display devices. Liquid crystal displays (LCDs) are used in watches, calculators, and laptop computer screens, and for instrumentation in cars, ships, and airplanes. Several types of LCDs exist. In general their value is due to the fact that the orientation of the molecules in a nematic phase substance can be altered by the application of an external electric field, and that liquid crystals are anisotropic fluids, that is, fluids whose physical properties depend on the direction of measurement. It is not pure liquid crystalline compounds that are used in LCDs, but liquid crystal mixtures having optimized properties.

The simplest LCDs that display letters and numbers have no internal light source. They make use of surrounding light, which is selectively reflected or absorbed. An LCD is analogous to a mirror that is made nonreflective at distinct places on its surface for a certain period. The main advantage of an LCD is low energy consumption. More advanced LCDs need back light, color filters, and advanced electronics to display complex figures. The best-known LCD is the so-called twisted nematic display.

Liquid Crystal Thermometers

The use of liquid crystals as temperature sensors is possible because of the selective reflection of light by chiral nematic (cholesteric) liquid crystals. A chiral nematic liquid crystal reflects light having a characteristic wavelength determined by its pitch and by the viewing angle (the angle between the eye of the observer and the surface of the liquid crystal). Because the pitch of a chiral nematic compound is temperature-dependent, observed color is a function of temperature. Liquid crystals can therefore serve as thermometers. By mixing chiral nematic compounds, thermometers can be customized to be effective in a desired temperature range. The color variation of some liquid crystal thermometers extends across the entire visible light spectrum within changes of a few tenths of a degree centigrade. For use in devices, microcapsules containing chiral nematic mixtures are mixed with binder materials. Liquid crystal thermometers find application in medicine (medical thermography). A liquid crystal thermometer attached to the skin can measure temperature variations of the skin. This can be useful in the detection of skin cancer, as tumors have different temperatures than surrounding tissues. In electronics, liquid crystal temperature sensors can pinpoint bad connections within a circuit board by detecting the characteristic local heating. The color changes of gadgets such as "mood rings" are a manifestation of chiral nematic mixtures.

SEE ALSO Inorganic Chemistry .

Koen Binnemans

Bibliography

Collings, Peter J. (1990). Liquid Crystals: Nature's Delicate Phase of Matter. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Collings, Peter J., and Hird, Michael (1997). Introduction to Liquid Crystals: Chemistry and Physics. London: Taylor and Francis.

Demus, Dietrich; Goodby, John; Gray, George W.; et al., eds. (1998). Handbook of Liquid Crystals, Vols. 1–3. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: