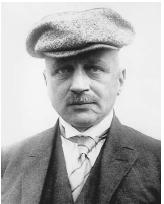

Fritz Haber

GERMAN PHYSICAL CHEMIST

1868–1934

Fritz Haber, born in Breslau, Prussia (now Wroclaw, Poland), successfully applied physical chemistry to technological problems. In 1918 he won the Nobel Prize in chemistry for his synthesis of ammonia from the elements, an important starting material in the production of fertilizers and explosives.

Haber, whose father was a natural dyestuff importer, was destined to enter the family business at a time when synthetic dyes began to dominate the market, and his fortunes soon floundered. In 1894 the young Haber became assistant to Hans Bunte at the Technical University of Karlsruhe. Self-taught in physical and electrochemistry, he applied these new theories with impressive results to chemical technology, particularly to the combustion of hydrocarbons, the electrolysis of salts, and the fixation of nitrogen. In 1906 he was appointed professor at Karlsruhe, but he left six years later to become director of the new Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry in Berlin. During World War I, that institute was transformed into Germany's headquarters for chemical weapons research and production, with Haber remaining as its director. When the Nazis in 1933 began to dismiss all Jews from civil service, Haber, himself a Jew who had converted to Christianity, immediately resigned and emigrated to Great Britain. He was invited to head the physical chemistry section of the new Weizmann Institute in Palestine, but died shortly before its establishment.

The most abundant component of common air, elementary nitrogen, stubbornly resists chemical reactions. However, certain bacteria can transform it to ammonia (the so-called fixation of nitrogen) as the essential raw material for protein production in plants. That was already known in the late nineteenth century when a rapidly growing population required a more efficient agriculture to be supported by fertilizers including "fixed nitrogen." At that time natural niter (KNO 3 ), or guano from Chile, was virtually the only nitrogen source for fertilizers, so chemists were challenged to find ways to fix nitrogen from the air. In the early 1900s, several prominent physical chemists, including Henri-Louis Le Châtelier, Friedrich Wilhelm Ostwald, and Walther Hermann Nernst, were experimentally and theoretically working on this issue from two different approaches to nitrogen: oxidation to nitrogen oxide and reduction with hydrogen to ammonia.

Although most researchers soon dropped the topic because of little success, from 1904 on Haber continued investigating both approaches under contract with the chemical company BASF (Badische Anilin- und Sodafabrik), who offered him money, equipment, and patent shares. The path to ammonia turned out to be more promising if the reaction rates were increased by catalysts at high temperature. Thermodynamics required low temperature, however, to move the equilibrium toward higher yields of ammonia. Because thermodynamics predicted the same effect at high pressure, Haber and his coworkers at BASF searched for temperature and pressure conditions that a reaction vessel could withstand and that resulted in acceptable yields. Success came only when they found more effective catalysts, at first with osmium and uranium. In addition, they pushed the equilibrium to the product side by continuously drawing off ammonia from the reaction mixture and continuously providing new reactants, resulting in 1909 in a steady flow reactor at about 100 atm and 500°C (932°F) with ammonia yields of some 10 percent.

Haber demonstrated that the production of ammonia from the elements was feasible in the laboratory, but it was up to Carl Bosch, a chemist and engineer at BASF, to transform the process into large-scale production. The industrial converter that Bosch and his coworkers created was completely revised, including a cheaper and more effective catalyst based on extensive studies in high-pressure catalytic reactions. This approach led to Bosch receiving the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1931, and the production of multimillion tons of fertilizer per year worldwide.

SEE ALSO Agricultural Chemistry ; Catalysis and Catalysts ; Equilibrium ; Le ChÂtelier, Henri ; Nernst, Walther Hermann ; Ostwald, Friedrich Wilhelm .

Joachim Schummer

Bibliography

Goran, Morris (1967). The Story of Fritz Haber. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Smil, Vaclav (2001). Enriching the Earth: Fritz Haber, Carl Bosch, and the Transformation of World Food Production. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Stoltzenberg, Dietrich (2003). Fritz Haber: Chemist, Nobel Laureate, German, Jew: A Biography. Philadelphia, PA: Chemical Heritage Press.

Travis, Anthony S. (1984). The High Pressure Chemists. Wembley, U.K.: Brent Schools & Industry Project.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: